Growing up Asian in Australia Tanveer Ahmed

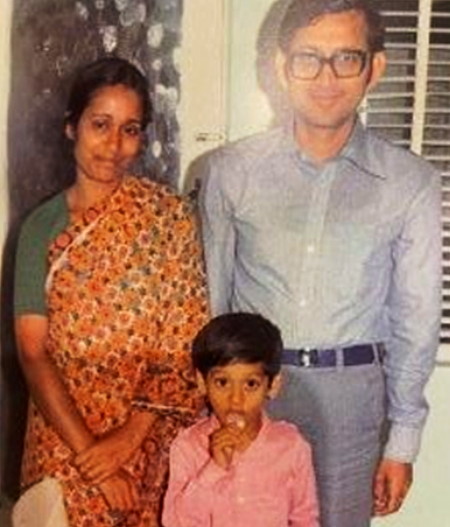

My dad still cut my hair once a month, a ritual we undertook while I sat on a stool on the bathroom floor. Each time he would remind me of how he cut his relatives’ hair while growing up in a small Bangladeshi village, a story that would coincide with another about him waking at dawn to sell rice at the local markets in order to fund his education.

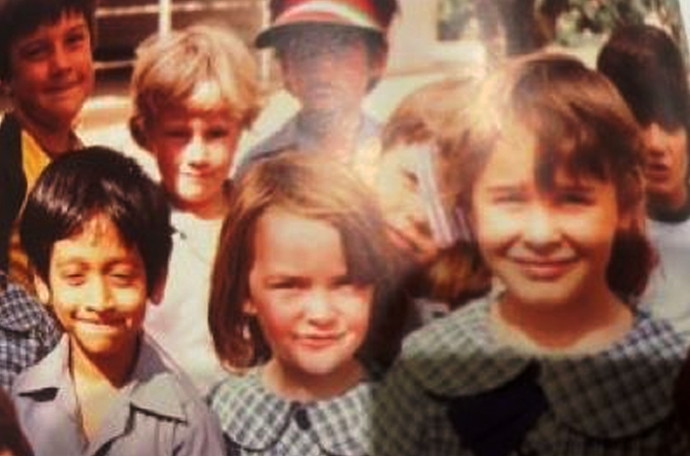

Lynchy advised me gently that my father’s foray into hairdressing had to stop. We were almost twelve years old and were beginning to take an interest in girls. My chances of meeting a girl were zip while my father was channeling 1970s rural Bangladeshi fashion through me. He would visit my house every day after school and we would ride our BMX bikes to the local creek. There we would play marbles, skim rocks across the water or play french cricket with a plastic bat. I had never visited Lynchy’s house. He always made excuses about his annoying older sister or that his parents didn’t like having guests. I didn’t push it. I thought my parents were annoying too and I was embarrassed that my house always smelt like curry. But Lynchy seemed to love hanging out at my house. He would sit with my adoring mother and talk about school. He helped her with making snacks and dipping doughy mixtures into Indian spices. He spoke of how all his family ate were rissoles, steak and baked potatoes. I looked at him with envy, wishing my mother could cook the items. She treated him like her long lost Aussie son, hand feeding him and stroking him across his blonde flat top. “You are a very nice boy, Darr-el.” she would say while patting him on the head. “Not like my son, who never eats his vegetable curry.” I never felt jealous. I knew my mother was just being nice, because she lamented how poorly Daryl performed in his studies. She would encourage us to do homework together, but the chances of that happening were slim. I can’t say I was ever disappointed. It was embarrassing to be good at studies and I tried to hide my scholastic abilities as much as possible. I even failed a couple of exams on purpose. The teachers freaked and thought about sending me to counseling. That was enough motivation to top the class again. But in the afternoons, once Lynchy had chowed down on his daily samosas, it was time to ride to the creek. That was all our suburb really had. Toongabbie it was called, home to the highest concentration of drug addicts, single mothers and ex cons in all of Sydney. I’m not sure there were Census figures to prove it, but everybody seemed sure about it. I would later attend a posh private school in the city and be known as Tanny from Toony. I took my tie and suit jacket off when I came off the train to walk home in fear of being abused. It even flooded when the creek overflowed. Some people thought we lived there because the poverty and flooding resembled Bangladesh. It was one of the very last days of our primary school days when Lynchy asked me to come over. I was shocked. It felt like some kind of goodbye before we headed off to high school. For all our talk of maintaining our friendship, I thought his invite was some kind of admission that it would be futile. “We’ll still see each other man,” I said, genuinely believing it. “I’ll still live in Toony.” Lynchy reassured me that it had nothing to do with it. It was his mum’s idea as a kind of repayment for all the food my mother had fed him. I nodded with approval. I had never been to his house, despite our long friendship. I longed to fulfil my wish of tasting the mouth watering promise of his family’s rissole, the delicate balance of mince, breadcrumbs and egg. I asked the local milk bar about it, but they said they didn’t cook it anymore. The fried, potato scallops or chiko rolls didn’t fulfil me in the same way. At last, my dream was to come true. And besides, the creek had dried up after months of no rain. I didn’t even bother going home, but walked to Lynchy’s white weatherboard house toward the train station. There was a front patio where his long haired, tattooed father used to sit and read car magazines, but had been empty for months. I had often walked past it and had seen his mother watering the garden, which consisted of a handful of red azaleas in a zigzag. She smiled but always looked like she had bigger worries in her life. His elder sister, Stacey, never paid much attention to me, once telling me that I was too short for any girls to like me.

Her comment helped me become a loyal sidekick to Lynchy’s lead role in the Stacey complaints commission. ‘Er, Stacey’s face is a zit factory’ or ‘Stacey is meeting her boyfriend at the parole office.’ That afternoon Stacey was busy at her work as a hairdresser. Only Lynchy’s mother was home. His father no longer lived there. Daryl had told me recently and I was confused and asked dumb questions about why. He told me about his parent’s separation a few months ago, while we sat by the creek and gave each other horsey bites, slapping each other on the leg. It was a rare tender moment between two boys entering manhood, except I had no comprehension what the hell divorce was. He said his parents fought a lot and his mum thought it was better they lived apart. He mentioned there was another woman involved. I didn’t get it because as far as I could see, my parents had nothing in common and barely had a relationship that I could tell of. When my parents first met before having an arranged marriage, my father, who was trained as an actuary, asked my mother a multiplication question to test her mathematical abilities. My father would just work in the garden, tell me to go and study while my mother did the housework and made my little sister and I eat all the time. My parents fought a lot too yet they seemed to have no problems staying together. But I worked out that it wasn’t a topic to dwell upon. Lynchy and I sat at a breakfast table and we were served green cordial. His mother asked me to call her Bridget. She had weathered, reptilian skin like many older Australians who had spent too much time in the sun. Her droopy eyes and furrowed forehead gave her a melancholy edge. I just thought she looked kind of sad. She patted me on the head like my mother did to Lynchy. I liked it. She told me I must have been really smart and wished me well at my new school. My parents never told me I was smart. I was thrilled. I had been to very few houses where non Bangladeshis lived. All my other friends were from other countries and we often defined ourselves in terms our difference to ‘Aussies’. There was the Filipino kid who loved basketball and couldn’t say F. “Puck you,” he would say when he became angry. His family loved Karaoke and could be heard singing on the weekends. I once ate tripe at their house without knowing. There was a guy from Thailand whose name was Jimmy Thai. His parents ran a restaurant. He was able to kick box in his teens and was also known for breaking wind on demand. Other kids would travel from all over the suburb to see him perform his biological feats of flatulence. A Turkish mate used to help his dad manage their mobile doner kebab store, run out of the back of a caravan. I used to love eating the meat they kept in their fridge while we played video games. I later learnt his father was on worker’s compensation for a neck injury, as was an uncle. I felt sorry for these Turks who seemed to disproportionately suffer injuries in car accidents. Aussies were definitely different, I thought to myself. Lynchy’s house had pets and smelt a bit like the dog, a big German shepherd that intermittently sniffed my shoes. They had an air conditioner and a soda stream machine. I was amazed. My parents would never buy such a wonderful thing like the sodastream. Bridget sensed my awe and offered me a fizzy orange drink from the machine. She dropped two ice cubes into a glass before I was allowed to taste a piece of heaven. We continued our conversation while his mother spoke of her garden and how hard it was to keep her azaleas alive in the heat. I was riveted. Daryl sat beside me quietly, looking as embarrassed as I felt when he was friendly with my mother. He rubbed his fingers through his hair and gloated that about being checked for head lice at school but coming out clean. Bridget patted him on his head before asking me questions. “Have you been back to Bangladesh Tanny?” she asked. Daryl had told her of my origins, after lengthy lessons at my place showing him where the country was on the map and how it was formed after repeated war with India and Pakistan. I told her yes and mentioned how I got diarrhoea all the time, but still enjoyed village life more than the crowded, dirty cities. Bridget laughed and wished she had traveled more. I looked at her short cropped hair with interest. My mother always kept her hair long. “Daryl’s father never had any interest in the world beyond, only his tools.” Lynchy bowed his head and a frown appeared. I felt embarrassed and sad for him as the jovial, friendly mood turned sour for an instant. Bridget patted him across his crewcut again and motioned to some food on a plate. “I put some rissoles in sandwiches for you two. Dig in.” Lynchy motioned towards me, a smile replacing his momentary sadness. He grabbed two and handed me one. We bit into them while sipping our sodastream manufactured soft drink. A rush came over me as I tasted the spice free rissole bursting across my taste buds. It was worth the wait. I saw Daryl a few more times that year, but we became more distant as our worlds grew apart. I was becoming preoccupied with a new world of studying Latin and singing hymns during assembly while Lynchy was coming to terms with barely seeing his Dad. By the end of the year, his mother decided to sell their house and move to the North Coast. I never saw him again. I still thought of Daryl often in my first year of high school, imagining him riding his bike wearing a black Led Zeppelin shirt by the beaches of his new home. After gentle urging on my part, my mother taught herself how to cook rissoles, although she would mix pieces of chilli and turmeric paste into them. |

Dr Tanveer Ahmed (Shuvo), son of Mr Afsar Ahmed, is a psychiatrist, columnist and author. This story of same title is also part of memoir published in 2011 and included in compilation “Growing Up Asian in Australia”, a text for study in Victorian high school syllabus.

Comments:

Bangladesh Australia Disaster Relief Committee AGM 2025

Bangladesh Australia Disaster Relief Committee AGM 2025