Looking Back Muhammad Alamgir Context

Interestingly, this was the third migration in my life. The first two were for political reasons, and this last one was for personal reasons. Looking back into the first exodus [Muslims leaving British India for Pakistan], I can recall fondly that my father decided to migrate to Pakistan immediately after its independence in 1947. For him it was a dream come true after long struggles against the British and the Hindu dominance. On the drop of a coin, he gave up all the luxuries he enjoyed in Kolkata, his ancestral home, and chose a very basic life as a refugee in Karachi. [My father was in the public service in Delhi, the capital city of the British Raj. So, he was transferred to Karachi, which became the capital of Pakistan]. As providence would have it, after two decades, I treaded the same path in 1971. I left Karachi as soon as a point of no return became a fait accompli in Bangladesh’s struggle against the hegemony of Pakistan. The subsequent nine months in the history of Bangladesh is written in blood. It witnessed mayhem and plunder of catastrophic proportions, resulting in a thorough decimation of the economic backbone of Bangladesh. [Memoir of 1971, an English article in my website alamgir.works]. Sadly, not withstanding all my zeal for an independent Bangladesh, I had to swallow the bitter pill of leaving my country in quest of a better future in Australia for my progeny. Here is a reminder to the youth that nothing comes cheaply. The path to our goal − any goal − is arduous, tortuous. Nothing is given to us on a silver platter. A direct experience of life tells us that our struggle is on two fronts: one, on the economic front; and the other, on the social front. On the economic front, education for an improved discernment and skill, determines our productivity, which in turn gives us a firm foothold in the race for wealth and wellbeing. It goes without saying that we have to overcome an endless competition in order to achieve and maintain our position in the workplace. Likewise, on the social front, interaction with people around us determines our acceptability and position in the social hierarchy. Speaking idealistically, man does not live on bread alone; hence, at times respect and recognition are dearer to us than wealth and possession. In short, struggle on both fronts goes hand in hand in shaping our identity in the society. Challenge Most Bangladeshis who migrated to Australia in those early days were professionals in various fields. Therefore, to settle down in a convenient location with easy access to schools, shops and transport did not pose a problem. Admittedly, language was a barrier for the majority, specially ladies. However, the first generation did adapt to the new situation of life pretty easily and smoothly. With innovative intelligence, Bangladeshi men and ladies found fulfilment in their quest for a better life. Likewise, the students excelled at every level of education, and were more competitive than their own parents. On the social front, Bangladeshis had a natural desire to form their own groups. [Association is the word Bengalees prefer. ‘Bengalee’ is a generic word indicating one whose language and culture is rooted in Bengal. Bangladeshi is one who comes from Bangladesh, a nation-state formed out of Bengal]. They tended to become close friends with their compatriots who spoke the same language and had the same culture at home. However, more often than not, they insisted on making those groups a little more formal than we find in other ethnic groups. They attached a way too much importance to who should be at the top of the hierarchy and who should carry the towel, as it were. Capable or not, when with their own people, they aspire to lead, not to be lead, i.e., they want to be the leaders, not workers. So, even though the number of Bangladeshis was only a handful, there was a persistent bickering at times and a constant smouldering at other times that kept them from achieving solidarity. The result was not something unexpected. Soon there were many groups, many breakaway splinters, as well as many lone dissenters who disappeared from the radar unnoticed. Once, the Sydney Morning Herald reported: “Bengalees love to differ”. It does not take a genius to grasp this truism. In order to claim distinction − a desire to be praised for what we have not done − sensitive as they are, Bangladeshis are known to take issues with claims to leadership, place of birth, etc., and exaggerate educational qualification, seniority in age, position at work, family connection, and last but not the least, value of their assets – personal or ancestral. Lo and behold! they sneak into the personal details of everyone near and far, yet they mystify their own secrets with great craft. Luckily, the new generation is not infested with these hangups. By the same token, the young are least bit interested in forming these imploding groups or meeting grounds. Therefore, they are drifting away from their first generation faster than one could realize. And this now is a visible phenomenon in the loosely knit Bangladeshi community. Looking back, we do acknowledge with great admiration, those whose readiness to come to the aid of fellow countrymen has been matchless. The most unique among them, one who has left behind fond memories in the hearts of many, was Dr Mokhlesur Rahman. [He received his highest degree in Microbiology from the New South Wales University, and spent his working life at the Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney].

We must appreciate that social life is a strange combination of expectations and uncertainties, hopes and disappointments, bravery and refrain, elation and irritation, and all other forms of highs and lows. In a dichotomy like that, it requires a great courage to remain positive, take the plunge, and contribute something for the benefit of the society. Again, looking back, Dr Fazlul Huq is one name that must be mentioned here who never abandoned the group in anything that the community aspired for. [A scholar of Chemistry who spent long years at the Sydney University as a facilitator to research students].

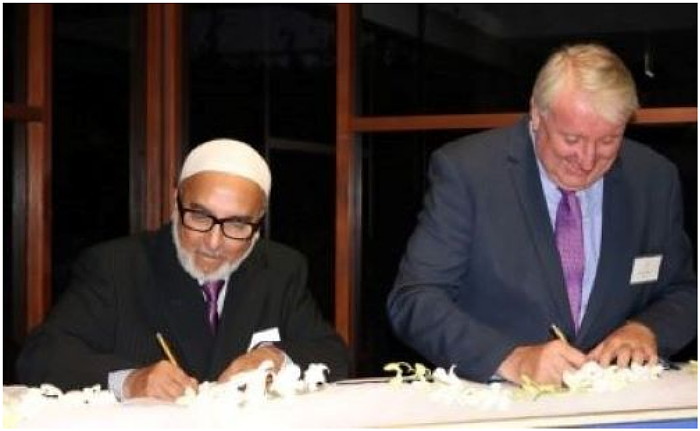

Islam As mentioned above, the common identity as a Bengalee was not good enough to keep us satisfied with each other. Sensitive in nature as we are, affiliations to political parties back home became another factor to keep alive the love-hate relationships with our own compatriots. So, looking back in those early times, Islam entered the scene as yet another issue to fight for. It’s a fact, that barring a few non-Muslims, Islam is the identity of the mainstream Bengalees in Sydney. However, first it was politics and then it was religion that became the major instruments to fracture the Bangladeshi community to the nth degree. We have to admit that in matters of dissension concerning Islamic practices, Bangladeshis are not alone. The entire landscape of the Muslim world presents the same picture. However, honestly speaking, to be divided into sects and sub-sects could be accepted as benign, because differences of opinion on issues of practice is rather human. By the same token, to turn away from fellow Muslims on the basis of petty matters, or to magnify such variations out of proportion, is certainly a stab in the back of the ailing Muslim Nation. [I.e., Muslim Ummah. See verse 10 of Surah Hujurat which gives the essential characteristics of Muslim Brotherhood]. Nevertheless, the saving grace is that there are those who engage themselves in good deeds like preaching, or in isolating themselves for extra devotion, or in sweating day and night to provide succour to the deprived, both here and back home. But such pastimes should not go to their heads. They do not have the license to hold others in contempt, or to secretly admire their own perceived honour and dignity. [In Arabic Ujb, self-conceit. While most moral defects could be likened to bacteria, i.e., curable, Ujb is the ultimate virus that eats away the value of all good deeds, and is very hard to cure]. By and large, Islam’s teaching of humble deportment is conspicuous by its absence, both among the high-ups and the lay. Still, looking back, not everything is lost. Today, among the Bangladeshis, Muslim men and ladies gather in many places to revive the teachings and learning of Islam in order to save the coming generations from falling apart. The vastly spread out Bangladeshi community is busy picking up the pieces of neglected knowledge and culture that reconnect us to Islam. With that in view, they have bought pieces of land in a number of places to build Masjids and Musalla. In addition to that, there are those who are working hand in hand with relevant authorities to look after the burial needs of the deceased − admittedly, a most difficult task, but forgotten nonetheless. Most notable among them in this regard is Kazi Khaliquzzaman Ali, a pioneer, whose single-minded dedication and sacrifices for the cause of Muslim burial is well-known to the entire Muslim community of Sydney, let alone the Bangladeshi Muslims.  Mr Kazi Ali signing the MoU with the CEO of the Catholic Metropolitan Cemeteries Trust securing 4,500 new burial spaces for Sydney’s Muslim community at Kemps Creek Cemetery in Sydney’s west. I recommend devoted Muslim youth to come forward and attach themselves to Kazi Khaliquzzaman Ali as his aide, and learn all the details that should be taken care of from the time of death to the final task of burying the dead. Indeed, that requires liaising with the coroner, paying for the funeral services, buying graves, and on occasions

Yet another group of devoted Muslims are working hard to find ways to help low-income Muslims to buy properties, or to collect funds to rescue people in times of distress. In this regard, the efforts of the illustrious Mufazzal Bhuiyan, who spent long years as a high official in the hospitality industry, comes to mind. Students of Islamic principles of Economics should take interest in this very challenging need of the time, learn from the experiences of these selfless promoters of charitable deeds, and put their heads together to find an equitable solution to money management that can bring ease to so many struggling Muslim families.

Again, budding economists may think of strengthening the hands of Aviation Maintenance Engineer Azadul Alam in setting up charitable funds with the holy intention of salvaging people in dire straits. Later day Migrants As said earlier, that the early migrants from Bangladesh were professionals in various fields, hence they prided themselves of being white collar workers. The chaos in the social hierarchy was rooted in their indulgence in an unspoken comparison between them to determine who was more important than who. As a result, barring a few bold efforts as illustrated in the previous sections, every social agenda was stymied from progressing smoothly. Looking back, Allah, the all-Wise, out of His infinite Mercy, brought about a change in this predicament of the Bangladeshi community. In due course, waves of enterprising Bengalees arrived, who showed us ways of how to be self-employed, instead of bragging of self-satisfying titles in the corporate sector. Today, scores of them are running profitable businesses in many parts of Sydney, employing thousands of their compatriots, who acquire right skills when presented with opportunities. Among these resourceful Bengalees are importers, retailers, real estate agents, tax and accounting consultants, freelance journalists, publishers of local newspapers, migration agents, interpreters, restaurant owners, specialized men in every aspect of the building industry, solicitors and doctors running independent practices, etc. Some have entered in State and Federal politics, and have earned for themselves a good standing, hitherto unheard of in the first generation of Bangladeshis in Australia. Our debt to Bangladesh Looking back, we have somehow steadied our ship from social, economic and religious perspectives − although lots of work still remain outstanding. Time has also come for all three generations of Bangladeshis to wake up to the reality that we can never repay our debt to the country we have come from. All the privileges that we enjoy today are the direct outcome of the endless sacrifices of our ancestors back home. [Please do not get bogged down with the rhetorics of what is our home, Australia or Bangladesh]. The fact that we are here, should be seen as an assignment, a responsibility, a pay back time. We must realize that we have left behind a large section of our own very close family who are still toiling ever harder to make their living; and by virtue of their efforts and sacrifices, the country is inching ahead in the race for survival against innumerable odds. Our generations growing up here in Australia must be made aware that three distinct sections of the population of Bangladesh earn bread and butter for the country. The chiefest of them are the contractual labour force who work their guts out in the harsh conditions of the Arab lands, Malaysia and southern Europe. Although the poorest in the social hierarchy, their contribution is the main source of direct revenue to the treasury of Bangladesh. The next in terms of volume of revenue is the contribution of the thousands of poor village girls who work in the garment industry. [Lovingly called Garment-Girls]. They too leave the comfort of the company of their dear families in the beautiful countryside of Bangladesh, and come to live in squalid shanties of the cities where most of the garment factories are situated. Indeed, the third, and no less important, are the peasants. They work in the fields tirelessly everyday of the year in the harshest conditions presented by the gruelling weather – rain, flood, heat and cold – to bring food to our tables. Often, their produce is blown away by storms, or washed away by bursting dams, or frozen in bitter cold, leaving them without food in their own kitchen. Without them we have no food, and yet they have remained poor eternally, and in the language of Economics, are getting poorer by every passing day. Once again, I recall Dr Mokhlesur Rahman, may Allah have Mercy on him, who set up an orphanage in his hometown in Bangladesh many years ago. His son Pushkin Rahman visits the place once or twice a year to supervise the effectiveness of the outfit.  Orphanage established by late Dr Mokhlesur Rahman at his home village in Bogra. Indeed, there are others who do similar charitable works for their folks in Bangladesh. I invite the youth to come forward and participate in this noble approach to life for the sake of dear Bangladesh. Undoubtedly, Bangladesh is the source of the success that has come their way. Therefore, whatever we do for Bangladesh is never enough. Indeed, this is a never ending task! To end my plea, I quote from our Book of Guidance. It says in verses 11 to 16 of Surah Balad: But he has made no haste, on the path that is steep. And what will explain to you the path that is steep? (It is) freeing the bondman. Or the giving of food in a day of privation, famine. Or the orphan with claims of relationship. Or to the indigent (down) in the dust. SO THINK! |

Comments:

Nomination Form is available at the end of the notice

Nomination Form is available at the end of the notice